EDGEPROP. 16TH MARCH: In Malaysia, the affordable housing segment is partly funded by the free-market housing that is priced to cover the outstanding cost of developing the former.

The Singapore housing has long been regarded as a role model of successful affordable housing ownership. Nearly 80% of Singaporeans live in public flats that are sold with a 99-year lease below market value, of which 90% own their own homes.

The Ministry of Local Government Development (KPKT) has voiced its intention to have exchange sessions with Singapore’s experts to help solve Malaysia’s affordable housing woes.

In fact, this is not the first time KPKT attempts to study and incorporate the Singapore’s pubic housing model within the local context. Back in 2018 during the Pakatan Harapan’s administration, the then KPKT minister conducted a three-day official visit to Singapore to learn the developments, plans, history and background that drive housing developments there.

However, the transferability of Singapore’s experience to Malaysia could be limited because the republic’s public housing achievements are driven by the following key factors:

- consistent political commitment

- compulsory land acquisition policies

- consolidated single-party execution

- effective housing finance system; which is the result of many macro-economic dependencies

All these require many policy or administrative realignments over a long time before it can be translated into the Malaysian context.

Consistent political commitment

In Singapore, public housing is not just a social welfare programme to shelter those who are unserved by private housing, but is a national development strategy by which socio-economic change and political control are exercised on the majority of the population. Public flats are built and sold at subsidised prices by the government. Over the last five decades, the Singaporean government has been funding state loans and grants for the development of public housing, which amounted to a total of approximately S$28 billion (about RM93.58 billion).

Since its citizens know the government relies on the success of its public housing for legitimacy of its rule, they, in turn, have confidence on the value of public flats and thus, are more inclined to purchase the subsidised flats, leading to a vast pool of demand that enables even more efficient capital allocation from the government. This, eventually, grants the government ability to control the demand and supply for affordable housing in the long run, as well as the stability of the overall housing market and prices.

Compulsory land acquisition policies

In order to develop subsidised public housing, the Singaporean government has instated a set of efficient land acquisition laws that empowers it to expropriate land for development or redevelopment. For example, the Land Acquisition Act in 1966, which was later amended, allows the acquisition of private land, with below-market-value compensation to the landowners.

Consequently, the government becomes a significant landowner that can leverage cheaper land price and land mass for public housing development, leading to more affordable housing development, as well as prevent speculation by internalising the increased value of undeveloped land.

Consolidated single-party execution

Singapore’s public housing model is extremely dependent on existing transparency and accountability measures embedded in the administrative system by a single entity – the Housing Development Board (HDB). Since the HDB has central power to plan and develop housing flats – provided with land, funds, legal powers and state support – the profit-seeking impact from private developers is diminished.

This has made possible the effective mass provision of public housing. A small jurisdiction, coupled with relatively homogeneous developable land and inhabitant demographics, have allowed minimal disparity in housing stock development as well as more standardised quality of living.

Effective housing finance system

In Singapore, both employers and employees contribute a certain percentage of the individual employee’s monthly salary towards the employee’s personal account in the Central Provident Fund (CPF). The contribution rate was 5% each when CPF was first established in 1955; but increased to 20% for employees and 17% for employers in 2016. Citizens can withdraw their CPF savings pre-retirement for down payments and mortgage payments for HDB flats under the HDB-CPR Scheme.

Since the returns on CPF savings are lower compared to the price increase in public flats, most citizens choose to withdraw their CPF savings to purchase public flats, especially when the government further relaxed the restrictions on the resale of public housing flats.

Affordable housing schemes in Singapore have thus been perceived as a viable means of alternative investment.

Cross-subsidisation – the biggest problem in Malaysia’s affordable housing development

Singapore’s model indicates that a government-driven ecosystem is crucial for the success of the country’s affordable housing development.

Like Singapore, the provision of adequate and affordable housing for the rakyat has long been the Malaysian government’s priority. However, unlike Singapore’s public-led initiative, the Malaysian private developers have been playing a critical role in building affordable housing for decades.

The private sector’s contribution includes not only the development of price-controlled social housing: low cost, low-medium cost, medium cost, and Rumah Mampu Milik (RMM) imposed as a quota by states in their planning approvals; but also comprising open-market units outside the stated category, whose market price is deemed affordable and in demand (between RM300,000 and RM500,000, depending on location).

In fact, Malaysia is the only country in the world where the private sector is imposed with compulsory affordable housing quota across the board nationwide. This quota differs from state to state, in terms of threshold of compliance, housing types and sizes, as well as prices and target markets; with a high quota of up to 70% and prices capped as low as RM42,000.

The construction of price-controlled social housing in Malaysia has been an ongoing challenge for developers, as its development cost is typically higher than the capped selling price of RM300,000 as stipulated in the National Affordable Housing Policy. The fulfilment of the quota can only be made through cross-subsidies, where the affordable housing segment is partly funded by the free-market housing that is priced to bridge the gap between the ceiling price and actual cost of developing the former. Depending on the land value and pricing of price-controlled units, cross-subsidies can be as much as RM100,000 per market-driven unit, or between 10% and 20% of its gross development value (GDV) on average.

While a contribution in lieu is permitted if a private developer cannot meet the quota requirement, it does not alleviate the problem of cross-subsidisation because the developers are left in no better position to offset the payments, except by fulfiling the quotas. Either way, cross-subsidisation from the free-market housing is unavoidable, as developers are required to bear the construction cost surplus of price-controlled units.

For instance, in Selangor, upon the approval for exemption from Rumah Selangorku (RSKU) provision, a developer can either:

- pay the total amount of selling prices of the exempted units

- hand over the land designated for RSKU development – including the provision of public facilities and infrastructure – to the state government or Lembaga Perumahan dan Hartanah Selangor (LPHS)

- build the exempted RSKU units on land owned by LPHS, in which the construction cost is based on the development value that has been exempted

The government should realise that financial viability is important in housing development, especially the development of affordable houses in urban prime areas that have higher land value. There is very little a developer can do with the land cost, especially in urban prime areas, as these areas have very attractive amenities and are limited in supply.

Also, there is little scope to reduce the construction and soft costs as both are determined by the free-market force and regulatory or industrial practices. More importantly, a certain amount of profit margin is needed to compensate the risk of undertaking high-cost activities in common housing development.

Given that a developer determines a project viability by maximising its revenue with the set land price, developers will then work out the maximum selling price of properties in order to deliver a housing unit just slightly under the cost of buying an established dwelling in the local market. If the resulting profit margin is satisfied after deducting costs, the project will likely be carried out. Otherwise, the selling price will be adjusted to ensure the acceptable level of profit margin is achieved.

Since affordable housing requirement quotas limit the revenue the land can generate, the construction of price-controlled social housing is only viable through cross-subsidisation by taxing on free-market houses. Consequently, the commercially rational response is to build high-end houses (above RM500,000) rather than median affordable houses (RM300,000–RM500,000).

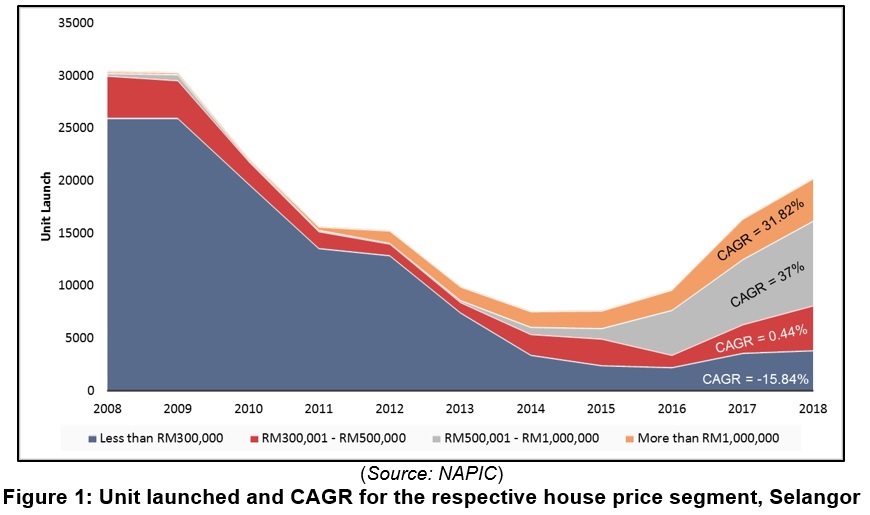

For example, there were not many launches of high-end houses in Selangor before 2015 (Figure 1) or before the quota was implemented and extended to include the construction of houses capped below RM300,000, which are targeted to serve the B40- and M40-income groups.

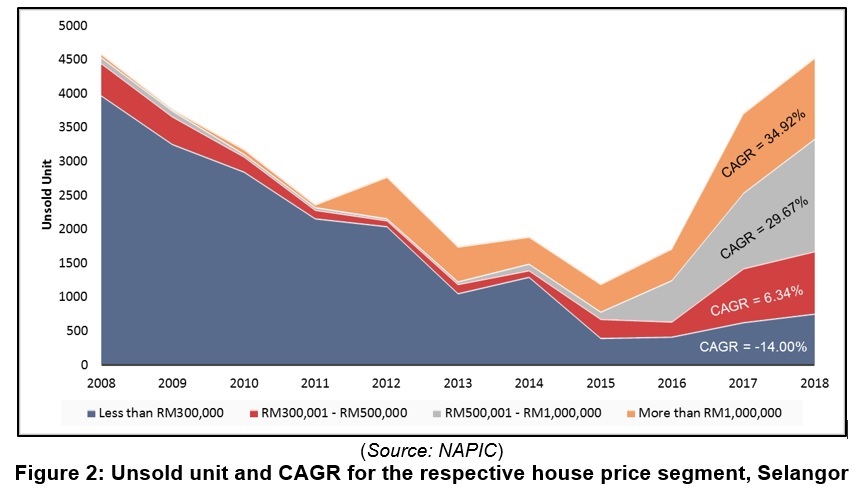

Following the surge in high-end houses, a drastic increase of overhang in this housing segment has been observed (Figure 2), which is then claimed as the main contributor to the state’s affordable housing crisis.

The phenomenon of overpricing should not be viewed as a skewed-market in favour of building expensive houses by profit-seeking developers; but a structural problem caused by the government’s affordable housing policy and a lack of government-led initiatives to deliver price-controlled houses on allocated public land. In the long run, this can lead to the cyclical problem of overpriced free-market housing products, which then further aggravates the issue of housing affordability in the country.

Towards a sustainable affordable housing development model

In planning a sustainable model for price-controlled social housing development, we need to abandon the current private sector-led cross-subsidy model.

The contribution in lieu for price-controlled social housing should be allowed as it can serve as an alternative to consistently generate funds that can be used to develop or to cushion the financial impact of building price-controlled units. However, its amount should not be set too high (such as a full compensation of the selling prices) to avoid any other form of cross-subsidisation that would worsen the country’s housing affordability.

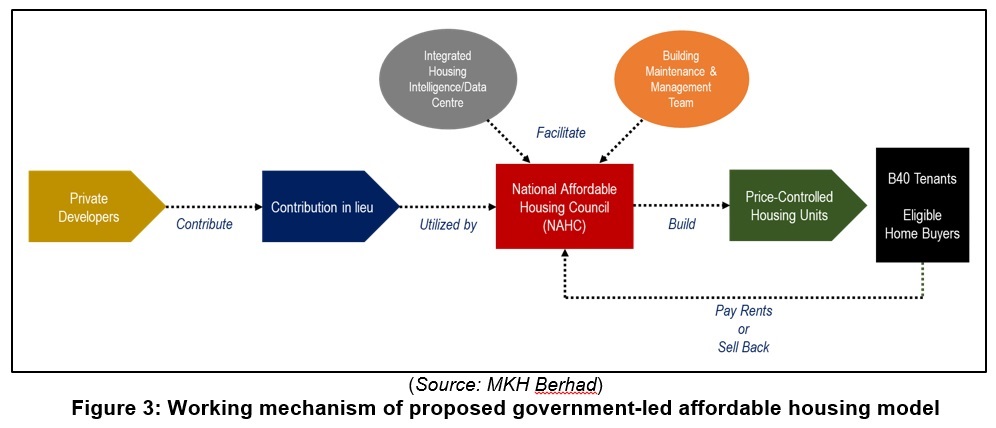

It is thus suggested that the private sector be made to pay contribution in lieu – let’s say 2.5% to 3% of GDV – for every approved free-market housing development that are priced above RM500,000, instead of physically building these quota units irrespective of land value, types and pricing of the free market housing.

This not only encourages developers to concentrate on the provision of median affordable houses targeted for the M40, but also to ensure the consistency of public housing development.

Most importantly, the private sector is free from building cross subsidised price-controlled units, as the contribution in lieu will be channelled to bear expenses on building price-controlled units.

A centralised agency or organisation should be established to focus on building 99-year lease price-controlled units in order to meet the national affordable housing agenda. This agency should be facilitated by an integrated housing data centre that monitors the supply of affordable housing in order to avoid any mismatch in terms of location, product, and pricing.

Besides that, a building maintenance and management team should be established to oversee and undertake the building management of all social housing to ensure they are in good condition when entering the sub-sale market.

Should the price-controlled units be sold in the sub-sale market, the gained profits should be capped at not more than a certain percentage of the original selling price – subject to the local property market – and can only be done after a moratorium of 10 years. This is to avoid any short-term speculation that hikes up the house prices, while also to allow genuine homeowners cum long-term investors to enjoy value appreciation of their properties when they upgrade to a free-market home. Upon expiry of the lease period, the government may consider renewing the master-lease for a further period, take ownership of land, or to release the master-lease without further legal obligations.

In view of the potential of rental housing as an alternative to homeownership, the government can also consider implementing the Affordable Rental Homes (ARH) Programme. A portion of the price-controlled social housing units can be set aside for rental purpose for pre-qualified B40 tenants, who can pay monthly rents of 7% to 9% of their household incomes.

Under the proposed government-led affordable housing model (Figure 3), the government no longer needs to suffer unsustainable financial losses when selling social housing or risk wasting resources on unsold and uncompleted units due to the consistent funding, more committed and transparent fund allocation, as well as better monitoring and control of affordable housing supply-demand system. Instead, the government can accumulate a sustainable and sizeable nationwide portfolio of RMM Contribution Fund Programme without depleting valuable government land bank.

More importantly, by freeing private developers from the affordable housing quotas, they are able to supply more good quality free-market houses to cater to market demands. Also, the gap of housing quality and affordability between public social housing and RMM schemes for B40 and M40 is addressed accordingly. Such a model can be seen as a win-win formula for all parties: government, homeowners and developers.